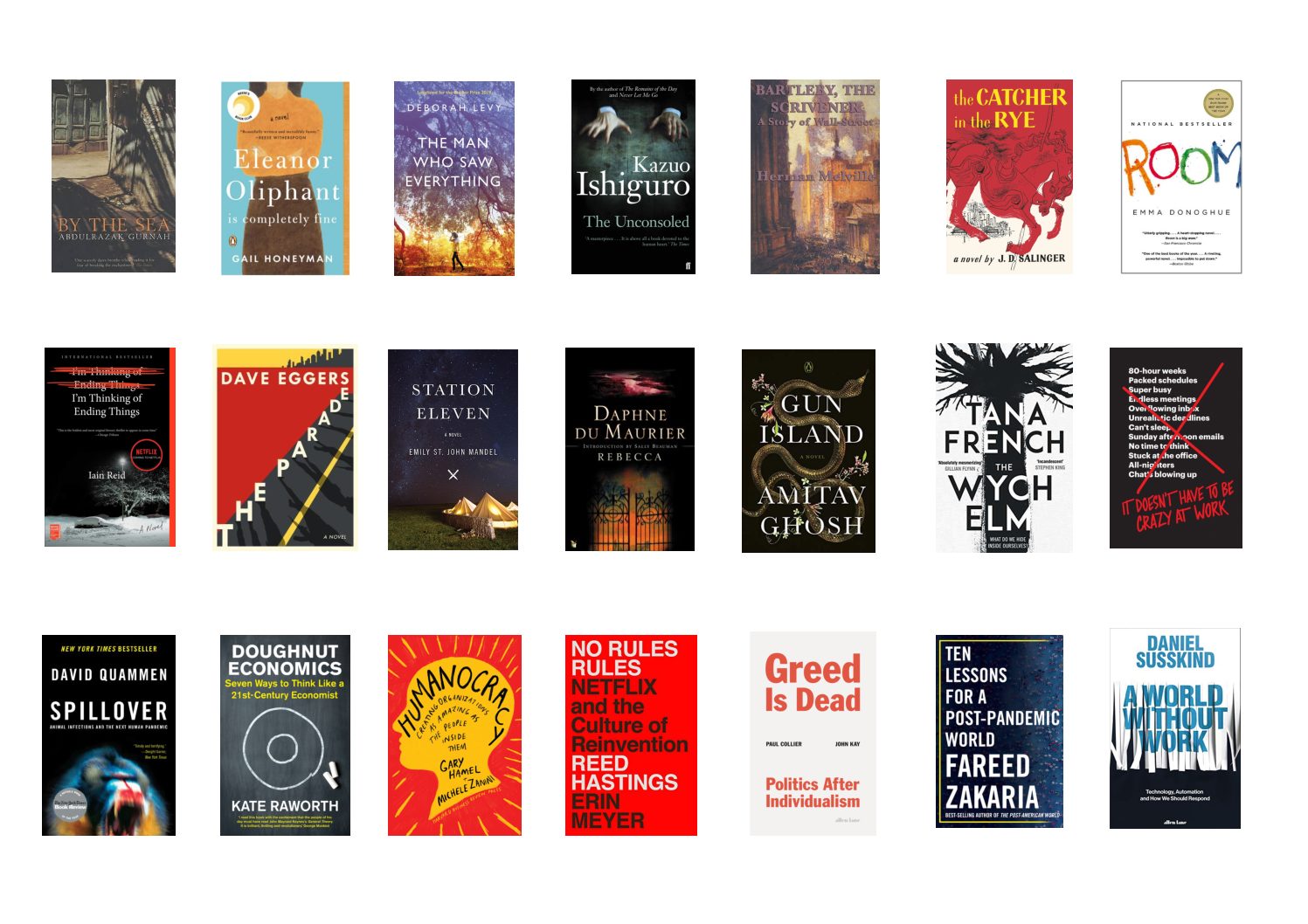

My top books of 2020

In 2020 I managed to pass a mark I previously thought unreachable – 100 books read in a calendar year. It’s been a very unusual year thanks to a certain virus, and an enforced pause sent me to my bookshelf even more than ever. Here are the best books I read, new and old.

My usual caveat: which books we love is very much a personal matter. This is not a list of books I recommend that you read; these are just my personal favourites from the past twelve months.

*************************************

Let’s start with FICTION. I enjoyed the following titles most of all in 2020:

By the Sea By Abdulrazak Gurnah

I picked up this magical book to reread on a trip to Zanzibar in January, just before the pandemic hit. It is about a family feud traversing two islands – it starts in a warm, tropical, spicy one and culminates in a cold, unwelcoming one. For me, quite simply one of the best novels ever written, about greed and revolution, truth and justice, home and exile. Mesmerising.

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman

It takes something special to create a book that is simultaneously uproariously funny and heartrendingly sad. Eleanor is an office worker, a loner, a maverick – and an alcoholic trying to obliterate her memories. She is completely fine, but also completely not. A wonderful book about the meaningfulness and meaninglessness of our lives.

The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy

A highly intriguing premise: a man is knocked down by a car in 1988. He is only superficially injured, and travels on to East Berlin and falls in love, but seems to be able to predict events that are yet to happen. The narrative breaks, and we now see the same man in 2016. He has just been run over on the same road – only this time his injuries are more serious. He swims in and out of consciousness, and we start to make sense of his memories. A life retold in fragments, with fractured relationships mirroring the breakup of nations. I’ll say no more, except that the man who saw everything actually saw nothing…

The Unconsoled by Kazuo Ishiguro

Another reread, by perhaps my favourite living author. A very difficult book to understand, about a famous pianist in a strange city, encountering some very strange behaviour all around him. I first read it in 1995, and was left perplexed. 25 years later, it all clicked. A truly marvellous book that explores an alternate reality, written in the style of a manic dream, about a celebrity life that has spun out of control.

Bartleby, the Scrivener by Herbert Melville

Just 50 pages long, and yet I have no qualms about putting it in my best books of the year. It is the sad tale of Bartleby, who works as a clerk in a law office and starts a little revolt by passively-aggressively repeating the classic line, “I would prefer not to” when given any instructions. Is he mentally ill, or just exercising his free will? As Bartleby’s life spirals downward, we are left wondering what was wrong with him – or what is wrong with us. Written in 1853, now regarded as a classic story ahead of its time.

The Catcher in the Rye by J D Salinger

Another classic that I could never get into when young. But wow – in 2020 I could finally see why it’s one of the most highly regarded novels of all time. Our cocky narrator is a rebellious teenager, perpetually in trouble, now on a binge in New York. He dismisses most people as phonies and hypocrites, but as he talks we uncover the real story, of a lonely and troubled misfit seeking simple human connection and never finding it.

Room by Emma Donoghue

An unsettling premise – a young woman and her young son held captive in a single room – executed flawlessly. This could have been a grim and depressing story, but the author pulls off the bravura feat of writing it in the voice of the five-year-old boy who has never known an outside world. A truly remarkable achievement that validates the strength of the human spirit.

I’m Thinking of Ending Things by Iain Reid

I reversed into this one, by watching the movie on Netflix first. Our narrator is on a road trip with her boyfriend. She says she wants to end things with him, but weirdly, her narrative keeps glitching. Time seems to shift back and forth. She never seems to be able to say the words to end the relationship…a clever and original work that is an atmospheric puzzle. I could do nothing else when I was reading it.

The Parade by Dave Eggers

The always interesting Mr Eggers pulls off another one. The Parade is set in an unnamed country coming out of civil war. Two foreign contractors are building a road using brand new technology, so that a celebratory parade can be held to unite the people. A slim, pared-down work that transports us to this troubled land, and imparts great lessons in ‘foreign assistance’ as our duo interact with the local people – with a gut-punch ending.

Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel

A book about a pandemic and its aftermath. The “Georgia Flu” is far more deadly than COVID-19 – it wipes out most of humanity. If you’re willing to pick this one up in these troubled times, you will find before you an exquisite work about a dystopian world that is not about carnage and destruction, but rather about art, hope and cooperation – all the things that make us human.

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

I first read this as a schoolboy, and revisited it in its 82nd year of publication. One of the world’s most famous books – and deservedly so. A young second wife moves into a remote mansion, and is troubled by the haunting presence of her glamorous predecessor, supposedly dead in a boating accident a few months earlier. Cleverly told back to front, a postmodern psychological mystery before such a thing was commonplace.

Gun Island by Amitav Ghosh

This new book by one of the world’s best-regarded contemporary authors is a complex story about climate change, the migrant crisis, and the meaning of myth and legend. A rare books dealer gets sucked into a sequence of events that takes him deep into the Sundarbans delta of Bengal, thence to wildfire-threatened California and finally to the sinking lagoons of Venice. All three places are skirting with environmental disaster. It is not without its flaws, but this is a heartfelt allegory about nature’s revenge for the greedy rampages of humankind.

The Wych Elm by Tana French

A chiller by one of the best current writers of crime fiction. This standalone book gets out us of the police precincts and deep into the life of a privileged dilettante who suffers a brutal crime and then goes to convalesce in his ancestral home with a dying uncle. Overwritten – it could have been way shorter – but still an intriguing study of what we think we know, and what actually occurred.

*************************************

My NON-FICTION shelf also gathered some riches this year. Here are the best of the bunch:

It Doesn’t Have to be Crazy at Work by Jason Fried & David Heinemeier Hansson

The founders of Basecamp let rip with this polemic that attacks the prevalent notion that you have to run an insanely competitive and stressful workplace in order to succeed. They don’t believe in stretch targets or obsessive benchmarking; they don’t pull routine all-nighters. Instead: they deliver great products and experiences; build a happy team; enjoy their work; get better every year. I run my own practice exactly like this, and loved this book. It brings sanity to the madhouse.

Spillover by David Quammen

2020 became the year of understanding viruses and pandemics, and I reached for many books to help shed some light on what just happened. This was the best of the bunch. Written in 2012, it is a gripping account of zoonotic diseases – the ones that spill over from nature and bedevil humans. Spoiler alert: the pathogens jump when we cause ecological disturbance – as we always do. Quammen called it on the novel coronavirus way back then – that a virus with high infectivity preceding notable symptoms would someday move through airports and cities like an angel of death. As the year ends, we are heading for 2 million fatalities.

Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth

At last, an economist who doesn’t believe it’s all about equations and regressions, charts and graphs. It leads the new wave to put people and planet at the heart of economics, and to make the goals of ending squalid poverty while protecting our only planetary home our key economic priorities. A book that brings heart and common sense back into a subject that has become obsessed with mathematical maximisations.

Humanocracy by Gary Hamel & Michele Zanini

A manifesto, no less, by two professors who went radical by asking the question: what matters more, organisations or the people inside them? This is a landmark work about killing the bureaucracies that negate our humanity and retard our progress. Ever wonder if we can run non-exploitative firms that devolve decision-making and allow people to partake and contribute? Read this book.

No Rules Rules by Reed Hastings & Erin Meyer

Netflix’s cofounder releases his first book about his trailblazing company, cowritten with an INSEAD professor. What’s the secret of their success? It’s the culture, stupid – and that’s what the entire book is about. This is one of the epoch’s most interesting companies, and the book spells out a powerful truth: if you want to innovate and take risks, you have to have a culture that drives that behaviour. Netflix’s culture is indeed unique: few controls, loose supervision, genuinely devolved decisions – but also, brutal standards and relentless feedback. It works for them; but you have to think about what might work for you.

Greed is Dead by John Kay & Paul Collier

Did someone ask for economists who display both head and heart? Here are two I have admired for a while, issuing a broadside against avarice and extreme individualism. Greed may not be dead, but it is no longer intellectually tenable as something to support and applaud. They rail against “the shrivelled view of society as a forum for transactions between autonomous individuals.” In our sterile ideological debates of left vs right and big state vs individual freedoms, what do we miss? The idea of community. “Individualism is loneliness, not liberation,” they remind us. Humans need to belong, and our institutions must foster that sense of communion and participation.

Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World by Fareed Zakaria

Fareed is one of our best seers and dot-connectors, and here he provides a reasoned summary of what will come after COVID-19 is done with us. A sweeping journey through the many disruptions and accelerations of the global pandemic, his book covers geopolitics and economics, knowledge and technology, power and society. An excellent primer to what’s coming.

A World Without Work by Daniel Susskind

What will we do when the machines can do most things better than we can, and there isn’t enough work for humans to do over the coming decades? This sober treatise warns us to take the threat of automation very seriously. A key insight is that we should not be complacent just because machines can never be human – they don’t have to be. They will outdo us in many tasks and professions by being intelligent in their own ways, not ours. This will throw up the huge challenge of how to give meaning and purpose to the lives of billions when paid work is removed from them. Read this to understand the world your children and their children will inhabit.

*************************************

So goodbye to this most challenging of years – but may 2021 bestow the gift of bibliophily on you and give you many happy and rewarding hours of reading.

Buy Sunny Bindra's new book

The X in CX

here »

Popular Posts

- NY’s wake-up call to the old guardNovember 9, 2025

- How to listen, really listenNovember 16, 2025

- Save your strength for repairsNovember 2, 2025

- Here’s why you should become foolishNovember 30, 2025

- Is AI hiring your company into oblivion?November 23, 2025