The ‘Uta do?’ culture that kills quality standards

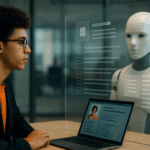

Whatever happened to “First-Time Quality?” It seems to have become an irrelevance in Kenya today.

The idea is simple enough. If you get something right the first time, you don’t have to incur the cost of inspections, revisits, rework or repeat jobs. If you pay acute attention and maintain a high standard when you do something, you will make a lot more money: because you’ll have a satisfied customer who will want to stay loyal to your company; and because you’ll cut out all the costs of redoing the work.

So what happened in Kenya? Why do so few business leaders impose the mantra of first-time quality on their teams? Why are we constantly fielding complaints and offering to redo things? I just don’t get it. Do we actually enjoy being second-rate, or what?

What is wrong with building contractors? They seem to routinely put up shoddy constructions, full of defects. They then spend months redoing the wiring, fixing obvious leaks, re-plastering walls that were done badly. Why? Why is it not possible to maintain a high standard every time you do something, so that you build your brand reputation and minimize the costs of reworking?

Why are utility companies constantly on the road, attending to leaks, blackouts and cut-offs – simply because they didn’t do something right in the first place? Why do power transformers keep breaking down, water pipes keep bursting, and roads have to be re-carpeted after every bit of rainfall? It’s not about the weather; it’s about the missing quality standard.

Consider the philosophy of “Zero Defects,” coined by management specialist Phil Crosby. Is such a thing even possible, you shout? Out here in Africa? Where so many things can go wrong?

Consider this: How many times have you mistakenly picked up the wrong child from school? Or erroneously paid out the wrong salary to an employee? Or inadvertently gotten into bed with the wrong spouse? Right here in oh-so-difficult Africa?

Not often, I bet. Those tasks are usually done just right the first time and every time, with great precision. Why? Because a bad outcome would be unthinkable. The attention is focused because the consequences are grave.

Our building contractors, utility providers and assorted other businesses are getting away with utterly slipshod quality, first time and every time, simply because the consequences are not grave enough. Bad quality doesn’t lose them business for many reasons: because their customers are docile and uncomplaining; because their competitors are often worse at this quality thing than they are; or because they are corrupt monopolists who routinely shout a rude and crude “Uta do?” to their customers.

This is a national shame. You don’t stand up to be counted in the world if your quality is slovenly. You don’t build international competitiveness; you don’t create a national export engine; you don’t command premium prices if you are content to play in the fourth division.

I fear too many of our organizations are all too happy to languish in the lower reaches, and neither their customers nor government regulators are demanding better. Take a look at the quality of buildings, roads, consumer products or hospitality offerings and you will understand why “Made in Kenya” is not a badge of honour; why we have a persistent trade deficit; why we produce such few world-beating enterprises.

We have to demand better. It is not good enough to spend our hard-earned money and taxes on people who can’t run their organizations properly. It is not good enough to fund the activities of cowboys and rogues. It is not good enough to look away from the corrupt practices that allow the slapdash and the slipshod to prosper unchecked.

Make it an issue in your life. This is a drum worth beating.

Buy Sunny Bindra's new book

The X in CX

here »

Popular Posts

- Make this your year of being boringJanuary 4, 2026

- Can we please stop with the corporate jargon?January 11, 2026

- Snakes and Ladders, AKA your lifeJanuary 25, 2026

- The man who passed by one markJanuary 18, 2026

- My books of the yearDecember 14, 2025