Does your business have a soul, or just spreadsheets?

I have a lot of time for James Daunt. He is the man trying valiantly to rescue the bookselling trade, against all odds. As a reader and writer I look on, gripped by the hope that bookstores can withstand the onslaught of online sellers and e-books.

James Daunt was once an investment banker. In his words: “Have you ever talked to a banker? Banker to banker, they have a lovely time. But for the rest of humanity, it’s just tiresome.” He walked away from that career to pursue a passion project: opening and running an independent bookstore in central London. He did so well in that unlikely escapade that he managed to build a mini-chain of six bookstores. Then came the big one: he was invited to take charge of Waterstones, Britain’s massive book chain with 3,000 employees.

Waterstones was close to bankruptcy when Daunt was recruited to save it. The book trade was sceptical. Daunt seemed more “sommelier than salesman”, as the New York Times put it—a little too erudite, a little too bookish to take hardcore business decisions. Or so they all thought. Daunt brought Waterstones out of its death spiral, returning it to profitability in 2015.

Across the pond in America, Barnes & Noble, once one of the book trade’s behemoth retailers, was also reeling from the digital wave. Again, new shareholders brought James Daunt in. After a massive clean-up exercise, his work is beginning to bear fruit. B&N actually plans to grow in 2023 by adding 30 stores to its portfolio.

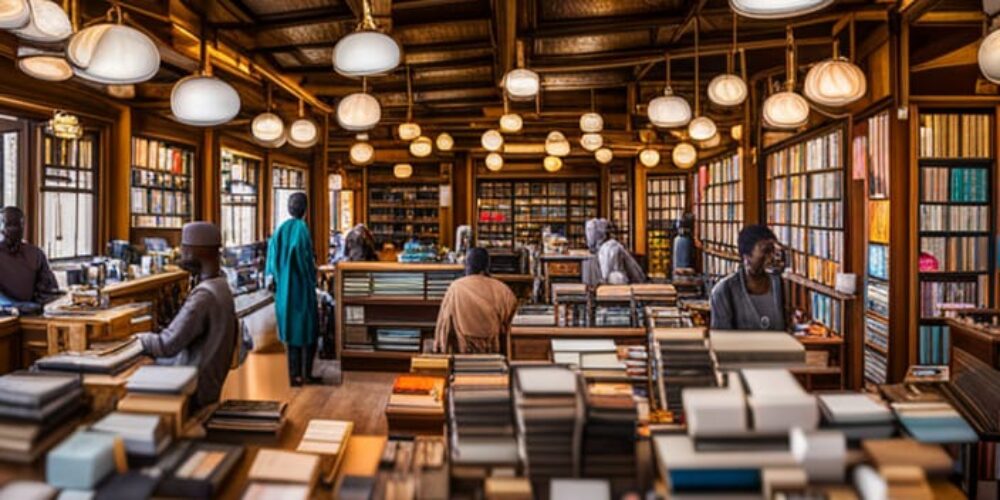

How does he do it? Now that is a very important question, for bibliophiles and business students alike. In a sentence, Daunt gives bookstores their soul back. He takes them back to what a bookshop actually is: a temple for booklovers, a place to spend time as well as money. Both Waterstones and B&N had become the opposite: heavily corporatized businesses ruled from head office. HQ would make all the key decisions, such as which books to stock and give prominence to. Every store looked almost exactly the same—which is just how control-freak group managers like it.

Daunt set about changing that, giving every store its unique identity back. He runs what often seem to be loose collections of independent bookstores, rather than a blandly homogenous chain of outlets.

I listened to Daunt talking to the BBC’s Stephen Sackur on HARDtalk, recently. When pushed to reveal his “secrets”, he pointed to just two things. If you hope to have your own successful business someday, or work in one that’s faltering, you may want to pay deep attention now.

His first point is that he had no theory about bookselling to lean on when he started. He learned it by doing it. The first “secret” is twenty years of hard grind: being in the shop, stocking and selling books, talking to customers, understanding their needs and patterns. It was trial and error. He tried stuff out, made mistakes, corrected them, got better and better—until he finally had a formula, of sorts.

(Incidentally, Sam Walton did exactly that in the US in the 1950s: he learned the supermarket trade by being a dukawalla, literally, for decades. He went on to turn Walmart into the global behemoth it is now—but only after much learning and unlearning, right there “kwa ground.”)

A second secret? Daunt returned the bookstores to booksellers. He believes passionately that bookselling is a vocation—something that you do because you love it, and which has its own unique peculiarities. It does not lend itself to merchandising and gimmickry. Booklovers are best sold to by other booklovers. Daunt has always culled his stores of generic assistants, and tried to focus his salary bill on a core of career booksellers. He has given them leeway to make stocking and displaying decisions, based on local buyer patterns rather than national algorithms.

And there you are. Business is idiosyncratic, and often deeply local. Investors, particularly of the private-equity variety, are obsessed with turning it into an efficient machine, selling the same product in the same way everywhere, and relying on textbook theories about scaling and growing. But local business remains stubbornly local; and all industries are defined by their own peculiarities. The businessfolk who create singularly excellent firms know this. They immerse themselves in these peculiarities; and they learn how to get better by trying things out. They put in the time and attention.

They also know a good business is always a team of like-minded individuals, not a small coterie of central honchos issuing commands to underlings and driving results through spreadsheets. The people in the business really, really matter. High personal engagement and long-term commitment is key. The best businesses employ people who love what they do; who feel wanted and appreciated; who can map out a career path; who develop special insider knowledge of the ins and outs and tricks and quirks of their industry.

Great businesses have a soul—a unique identity and personified principles. The rest? They pile ‘em high and sell ‘em cheap, until someone else can pile ‘em even higher and sell ‘em even cheaper.

(Sunday Nation, 23 April 2023)

Buy Sunny Bindra's new book

The X in CX

here »

Popular Posts

- How things fall apartFebruary 8, 2026

- Why the third generation might ruin everythingFebruary 15, 2026

- Pretty isn’t the productFebruary 1, 2026

- You don’t need people skillsFebruary 22, 2026

- Our connection with nature is elementalMarch 1, 2026