Why letting go of power and position is so hard for so many

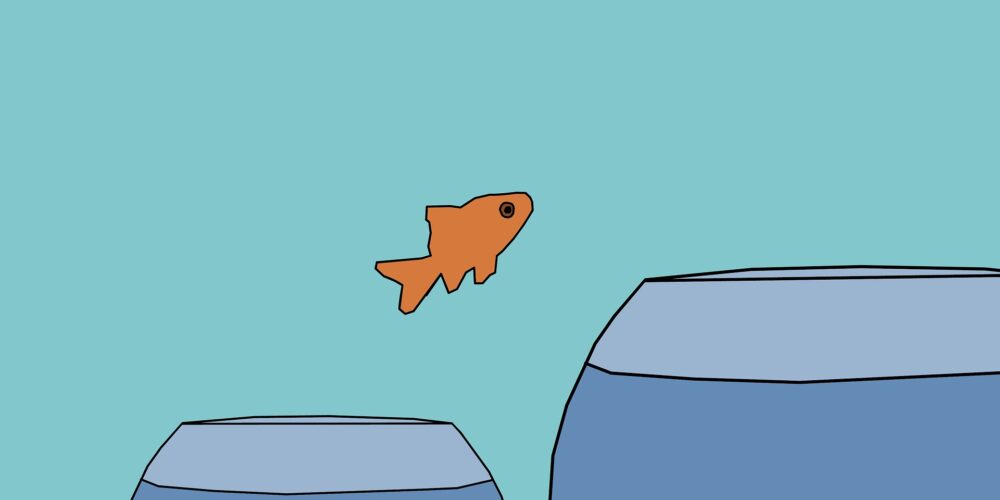

Last week I discussed the problem of leadership transitions in family firms. Many founders are unable to make meaningful handovers to new leaders, from either within or outside the business. This problem of refusing to let go of the reins, however, is not confined to family businesses. Let’s take a wider look at the issue this week.

Political leaders, particularly in our part of the world, also seem to find it enormously difficult to let go of leadership. They appear to imagine that their country depends crucially on their continued presence in power; they conflate entire nations with their own interests. They hang on and on, rigging elections, changing constitutions, creating crises, sparking wars—all for their own continuity. Some have been in power since I was in school. The nation often suffers severe retardation because of this stubborn megalomania.

Around the world, the long-lived leader is often a thing—and it is rarely a good thing, even in the corporate world. Coca-Cola’s iconic early boss, Robert Woodruff, became president at 33, and held that position for 32 years. Even after handing over the executive reins, he continued to dominate the board’s decisions despite suffering from debilitating strokes in older age, all the way to his death at the age of 95.

Don’t get me wrong: a long tenure can sometimes lead to enormous uplift for all. Some of those who serve for decades are undoubtedly brilliant leaders who govern their people well or take their businesses to breathtaking heights. The difficulty arises when they can’t let go. What’s the problem with that? Biology, for one thing—they suffer cognitive decline and physical deterioration while still sitting in the hot seat. Strategic irrelevance, for another—changes in technology and societal behaviour leave them struggling to keep up.

It is a common phenomenon, in politics and business. Why do so many hang on, even when facing growing loss of credibility? It is not that CEOs do not know the need to have bench strength in the organization. They will certainly pay lip service to the concepts of sensible succession—but will do little to strengthen the process. Margaret Heffernan, a CEO, author, and educator herself, had an insightful answer in the Financial Times recently. She quotes Dr Mark Goulston, an executive coach and former professor of psychiatry, who tells us that if leaders lose a job that is too rigidly connected to their identity, they will “literally fall apart, and feel useless, purposeless and worthless.”

Ms Heffernan told the FT’s Isabel Berwick:“Whereas normal people might approach retirement thinking ‘at last I can do all those things I always wanted to do but had no time for’, these individuals do not have anything they always wanted to do.”

That nails it. In my own work with chief executives, I often see this problem: there is no life other than this one. There is no notion of nourishment that comes from anything other than the current work. Even if this person were given time to do anything they wanted, there is nothing else they would want to do. Their entire life and meaning is wrapped up in the here and now—leading this entity or this nation, in this particular way. There is no meaning in anything else.

Indeed, the work is an addiction. The adrenaline and long hours and power and status become drugs, so much a part of the leader’s identity that retirement is a threat to be resisted and denied. They may be rich financially, but their retired life will not hold any riches for them. This looks like it is particularly a male problem, because men are more likely to make work the core part of their identity. Women tend to have richer, more rounded lives, while men are often found running in one deep, long furrow, never peering out over the edges to look at other things. In the end, they often have to be carried out of the singular groove that was the be-all and end-all of their lives.

Yet life is so rich. It has so many delights available, so much contribution we can make in so many diverse ways. To narrow it down to just one thing—the propagation of your own leadership in the very same place, doing the very same thing, for as long as you are alive—seems like an enormous waste. The thoughtful leader keeps an active interest in many things—hobbies, pastimes, relationships, challenges—from an early age. In the multifaceted life, letting go becomes merely a reshaping and a change in emphasis—not a scary and traumatic upheaval.

A final point concerns humility. None of us should imagine that we are so indispensable that what we built cannot continue without us. We are all specks on a speck. Our individual lives—no matter how seemingly impactful once upon a time—are, in the final analysis, trivial. They are also bounded by time. When your time is up, blow the whistle yourself and walk away. And do it while they’re still clapping.

(Sunday Nation, 14 May 2023)

Buy Sunny Bindra's new book

The X in CX

here »

Popular Posts

- Why the third generation might ruin everythingFebruary 15, 2026

- Results, not roll callMarch 8, 2026

- Our connection with nature is elementalMarch 1, 2026

- You don’t need people skillsFebruary 22, 2026

- How things fall apartFebruary 8, 2026